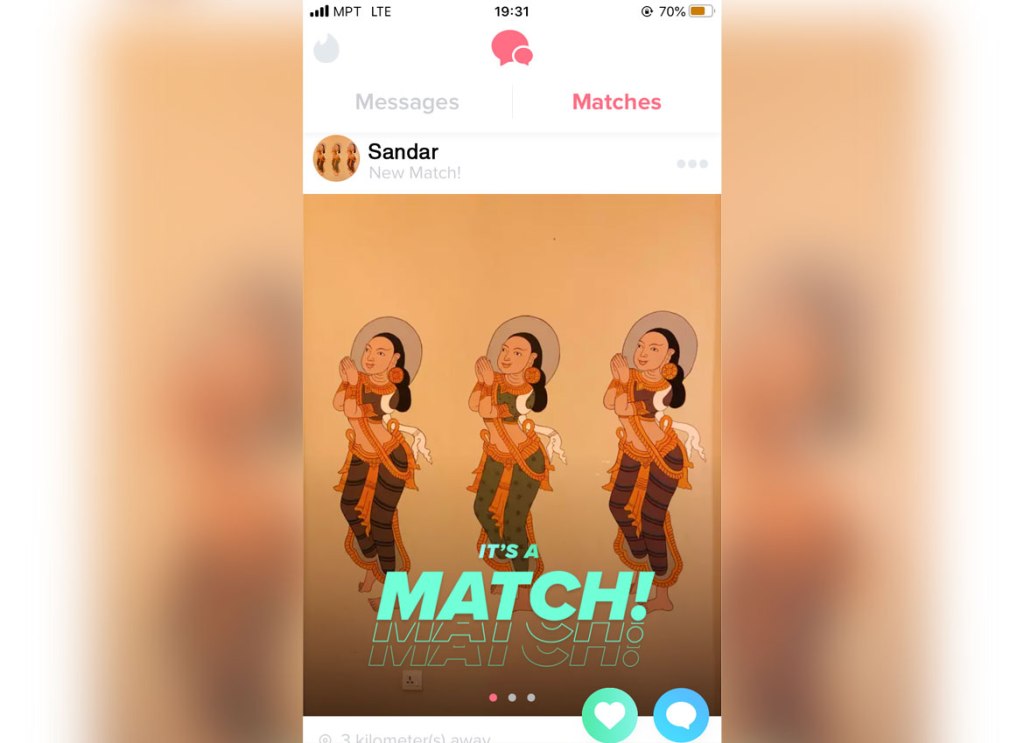

Myanmar matches with the new swipe culture

36-year-old Sandar Win chats with her two friends at Amazon Coffee, distracting herself with a smartphone in one hand. She smiles and flashes them a picture of a man called “Simon,” who’s 41 and is sitting on the back of a jet ski.

“Not bad,” her friends say. “Where’s he from?”

She swipes across two more images of the Asian gentleman—one with him wearing a tank top, showing off a scaly-dragon tattoo, and another a close-up of him smiling as a Yorkshire terrier licks his face.

“Is he Myanmar?” she asks. The girls scrutinize the profile, then debate three distinct possibilities—either a Myanmar repat with a bad-boy tattoo inked in Hong Kong, a Chinese-born American out for some fun, or a local boy hoping to mingle with some foreign ladies.

These are just some of the questions single women are asking themselves in the digital and increasingly globalized world of dating.

New technology, new possibilities

Tinder is still a novelty in Myanmar—many users have only been introduced to the app through a friend in the past year or so. Most people have never even heard of it, according to Sandar Win.

After recently ending a 7-year marriage, Sandar decided to follow her friend’s advice and install the matchmaking app on her phone.

“I was useless at first. I was all messy with my swiping, and I didn’t even know what a match was or that someone had messaged me,” Sanders said. “I had to Google how to use it properly.”

Sandar estimates that around 35% of users she views are local men, and 65% are foreign—either travelers or expats who work in Myanmar. Of those foreigners, she mentions matching with some scammers pretending to be in the military, asking her for money.

As with her friends, Sandar’s primary enjoyment in the app is a social one—she enjoys meeting new people and hearing about their past relationships. Not discounting the possibility of meeting Mr. Right, she was surprised when one user (a Myanmar guy) asked her directly to “hook up” (casual sex, otherwise known as a “one-night stand”).

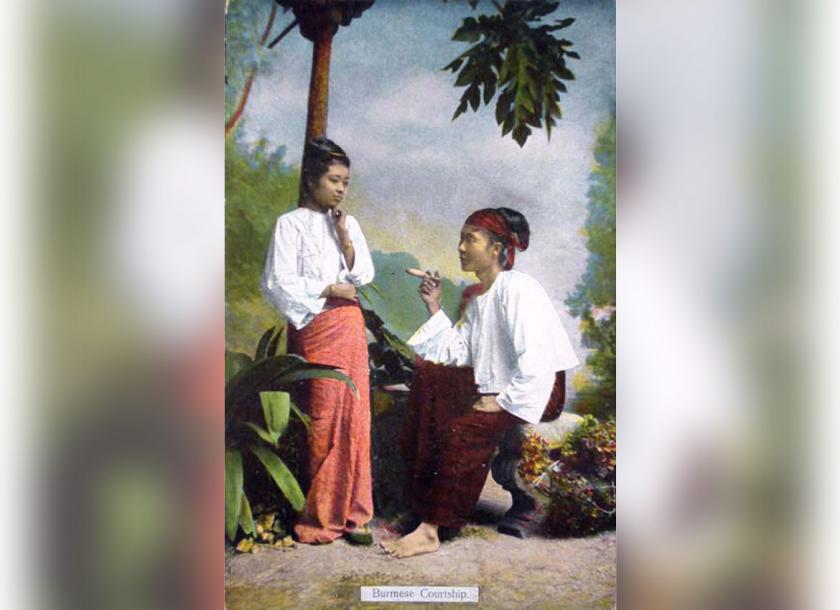

Dating and mating, the traditional way

Back in the 1980s, Sandar’s parents met the more traditional way, like millions of Myanmar couples still do today. It all started with a love letter (“yisar sar”), which her father (U Kyaw Tun) sent to her mother (Daw May San) after they’d attended the same university botany class.

Today the love letter is more likely to be a meme sent via messenger or a tag on a romantic song posted to Facebook. In Myanmar this courtship ritual is as timeless as the temples of Bagan, as golden as the gold at Shwedagon, and as considerably more complicated than swiping right on a smartphone.

Melford Spiro’s 1978 book Kinship and Marriage in Burma describes this ritual nicely, though his anthropological account deflates the romanticism somewhat: “they always confirm to a rather stilted stereotype,” for example, “’I love you … From the very beginning, when I first saw you, I loved you, etc.’”

U Kyaw Tun claims to have been more original in his love letters, making reference to the flowers of Upper Burma, the subject of their final college class together—the frangipanis and cherry blossoms of Shan State, perhaps?

Spiro’s book was written 40 years ago, but the principles of courtship in Myanmar remain the same. Dating Myanmar-style is very indirect, as Spiro notes:

To tell her directly of his love would be unthinkable, for that is tantamount to saying he wishes to have intercourse with her; and to seek her out in private is equally impossible for, until they are engaged, the girl will avoid him because, should he as much as touch her, her name is destroyed (na-me pyette).

What’s more, the young man never gifts the girl the love letter in person, but sends it via an “aung thwe” (matchmaker)—usually an older sister or aunt.

In U Kyaw Tun’s case, Sandar’s aunt was the aung thwe, delivering U Kyaw’s short love letter, penned on the back of an Inya Lake postcard. Both couples’ parents eventually met, and after two years of discussing the practicalities of marriage, Sandar’s parents finally tied the knot.

The love letter tradition of courtship, which may involve many months of back-and-forth, is the very antithesis of the Tinder date.

“I think my parents would get along with anyone I dated, but many Myanmar parents still won’t approve of Tinder or dating sites. They don’t really like the idea of their daughters meeting new people, especially by themselves,” Sandar Win said.

The old meets the new, and the foreign

Edgar is a 25-year-old finance analyst from England who started using Tinder Passport, a subscription-based service for travelers, before arriving in Myanmar two years ago.

Being a young man, and a foreign one at that, his experiences (and perhaps expectations) are different from Sandar’s. Coming from a country where over a quarter of young couples had formed relationships via dating apps, he says, “Myanmar women still seem very reluctant to meet up.”

“The biggest barrier for them seems to be their living situation. They’re either living with their parents or staying at places that have curfews.” Echoing Sandar’s comments, it seems that parents still play a central role in shaping young peoples’ attitudes towards courtship.

Edgar claims that around half of the female profiles on Myanmar’s Tinder are foreigners (mainly Thai and Filipina travelers), though most of his “dates” have been local women. He also noted that there were a considerable number of “ladyboys” from those two countries, though he wasn’t interested in meeting them.

Out of the women he did date, Edgar estimated that around 70 percent were Burmese, 20 percent Myanmar-born Chinese, and 10 percent Kachin.

“In the other countries I’ve visited it’s much easier to chat with women on Tinder and via WhatsApp or Viber, but harder to arrange dates. In Myanmar it seems the opposite—women are reluctant to message you at first, but when they do, they usually always want to meet up,” he said.

Other expat Tinder users also mentioned matching with women who offered home massage services (presumably a cover for prostitution) or sent links to their Instagram accounts.

Crossing the rubicon

Match Group, the American Internet company that owns sites like OKCupid and Match.com, estimates that Asia will comprise 25 percent of Tinder’s revenue by 2023—according to an article in the Bangkok Post. That’s certainly feasible, as online dating services in places like Thailand, the Philippines, and Hong Kong take off.

That number is unlikely to include a great deal of Myanmar users, despite the small number of new Tinder devotees like Sandar and her friends.

Taboos around dating and even meeting members of the opposite sex are still strong in Myanmar. The “hook-up” proposal Sandar was offered would be unthinkable in the real world but represents a new world of possibility (for better or worse) for some of Myanmar’s Tinder users.

For those who do use the service, it’s like crossing the Rubicon—with no guidelines or rules to navigate the journey.

Sandar eventually swiped left on poor Simon, citing his lack of an introduction as the deciding factor. She’ll never know if he was Mr. Right, though she eagerly awaits her next date—a foreigner who works in the media.

How she’ll fare? Read my next article to find out…

This article was published in The Myanmar Times

Leave a comment